Kenosis, the title of the Oficial Section of Fotonoviembre 2017, is based on the use Jacques Derrida made of the term in an interview with the theorist of photography Hubertus von Amelunxen and the media theorist Michael Wetzel. The philosopher defines painting, photography, literature and drawing as cenotaphs of something that has happened, that no longer exists. As the preservation of something lost. Derrida said “one keeps the archive of ‘some thing’ (of someone as some thing) which took place once and is lost, that one keeps as such, as the unkept, in short, a sort of cenotaph: an empty tomb. But are there any tombs that are not cenotaphs? And is there anything photographic [de la photographie] without kenosis?”1

Etymologically, Kenosis comes from κενό, the Greek word for emptiness. St Paul of Tarsus used it to speak of how Jesus Christ divested himself of his divinity in order to subject himself to the will of God the father. Theologically, it has been the source of controversy since it was used, for instance, by Luther, as one of the elements on which to restructure the believer’s position with respect to God. For the German monk, it justified the shift from a theocratic to an anthropocentric vision. If we were to apply the simile to our position on the image, we would be forced to divest ourselves of the whole apparatus that makes us see how we see, and the exercise soon becomes hugely complex because, after all, what is this apparatus?

Otherwise, Derrida’s de nition could be understood from the viewpoint of nostalgia for something that has happened and will never occur again in the same way. But what we are really interested in is another semantic dimension: If images are cenotaphs, then where is the corpse? What happened the body? What is the story and the foundation that sustains this army of zombies of which all we see are their memories?

1 Derrida, J. (2010) Copy, Archive, Signature, A Conversation on Photography. Stanford University Press.

The process prior to the formalization of Kenosis was based on three photos. In front of them, the spectator must remain on alert: the first is a view of the battleship USS Maine sunk in the port of Havana (1898); the second shows the poet Domingo López Torres alongside André Breton, Jacqueline Lamba and Benjamin Péret during a visit to the Canary Islands (1935) and the third is a still from Gordon Matta-Clark’s Conical intersect (1975). In them, the represented seems to be vying with its contrary, which is to say, if in the first photo the outward defeat is no more than a prelude to a victory that was the starting signal for the colonial expansion of the USA, the other two, on the contrary, show the absolute failure that lies in what would appear to be a victory. López Torres was assassinated just a few months later, in 1936, partly for the provincial cosmopolitism seemingly portrayed in the photo, while the third, Conical Intersect, conceals the paradox of how, once recorded as images, actions to protest against contemporary urban speculation are turned into commodities for the voracious art market. As such, each and every one of the exhibitions included in Kenosis ought to be understood as exercises in pursuit of the dismantling of the image. What form is adopted by what is not represented? How does the archive sustain narratives and change meanings? What lives on in the image? What is truthful when truthfulness seems to be an intrinsic quality of photography? It is precisely in this act of emptying, in Kenosis, where we encourage the need to keep resignifying what we see. In this way we give a little more life to this army of absent zombies.

Pecio del Maine remolcado fuera del Puerto de la Habana (1913)

Gordon Matta-Clark, Conical Intersect (1975) eai

Una cierta investigación sobre las imágenes:Building Ghost Transmission

Teresa Margolles, Vaporización (2001)

We are part of a “pixeled” world. When we transfer an action, it makes us think about its outer appearance and dislocation and we try to understand without seeing what is behind it. Photography is a language that records with light; it is the art and technique of fixing an action, of projecting images and capturing them. It is the conversion of electronic signals, the act of obtaining and returning a result; it is a perception device that transfers. Where are we in relation to a latent image that was never xed? What did we decide to reveal and what did we decide to keep hidden? Are we able to live with the latent image in the same way as with xed images?

Una cierta investigación sobre las imágenes [Certain Research into Images] is an essay whose structure contains the absence of a final word, of an end. On one hand, the framework is the underlying foundation that sets the guidelines for a conversation built on suspicions. On the other, its form is the gesture of witnessing said conversation and sharing it in order to experiment with the presence of absence. The challenge is not to let the uncertainty provoked by the image and the process of its cosmology (print, trace, burn, develop, copy) be confused with a hypothetical realm.

9th November 2017 to 4th March 2018

TEA Tenerife Espacio de las Artes. Sala B

Avda. San Sebastián, 10. Santa Cruz de Tenerife. Tel: 922 849 090 Horario: M-D de 10:00 a 20:00 h.

Artists: Carolina Caycedo, Raimond Chaves & Gilda Mantilla, Céline Condorelli, Alia Farid, Harun Farocki, Luca Frei, Jorge González, Teresa Margolles, Silvia Navarro, Diego del Pozo y Walid Raad.

Curated by Michy Marxuach

The infinite archive: documents, monuments and mementos

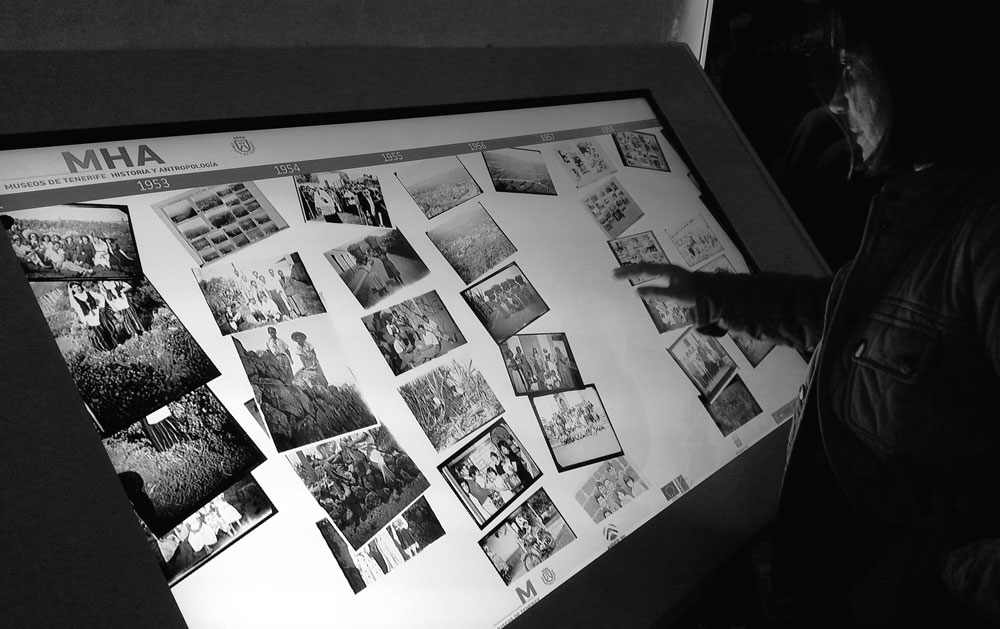

Exposición sobre el Archivo Fotográfico Vicente P. Melián. Museo de Historia y Antropología de Tenerife, Casa de Carta. OAMC.

Modernism has left a heavy baggage of nostalgia and, with it, an obsession with the document that induces the emotion of remembrance and tempers the fear of forgetting. We believe that by safeguarding it in archives that we have assured its testimonial value and guaranteed the future of the past. However, there is nothing stable in the archive. As a document and as a monument, as a metaphor and a recurrent sign of memory, the archive takes place as a circular route, without a beginning or end. Travelled once and again, classified and reclassified, it is always subject to multiple reinterpretations, to new internal elaborations and to increasingly more overwhelming dimensions

Photo frames, albums, reels and spools, memory cards, databanks of images, webs, clouds… Trapped by the images which are intended to prevent us from forgetting, the possibility of losing them forever produces a sense of anxiety. But the same images do not always evoke the same memories, and that is why we are obsessed with how they are archived. Organised with increasingly more sophisticated resources, our most highly appreciated images are mementos, injunctions not to forget what we were or what we had. Be that as it may, one remembers much better by sharing memories, exchanging them, renewing them and constructing our memories and our omissions together.

9th November 2017 to 4th March 2018

TEA Tenerife Espacio de las Artes. Sala B

Avda. San Sebastián, 10. Santa Cruz de Tenerife. Tel: 922 849 090 Horario: M-D de 10:00 a 20:00 h.

Team: Patricia Vara, Simone Marin y David Zuera.

Curated by Mayte Henríquez

Intersecciones Criollas [Creole Intersections]

Teresa Arozena, Despacho de Fernando Estévez. Departamento de Sociología y Antropología ULL 8 de abril 2017 (2017)

However, both the actual materiality of the archive and its very symbolic power have often been concealed between asking or reading.1

Originally, the world Creole alluded to the descendants of the white settlers that had been born in the American colonies. In its etymology, the term incorporates both the notion of displacement and the need to adjust to a new place. Paradoxically, however, in an eclipse of sorts, the word gradually acquired different albeit incidental meanings, depending on the social and geographic contexts of usage.

Intersecciones criollas is a brief overview of images that have been part of a recurrent and reiterated gallery of contemporary life in the Canaries, without them being necessarily Canarian as such, and that seem redolent of a closed reading of the Islands’ cultural history. That said, each one of these images would appear to include layers that are activated or de-activated depending on the space they occupy and how they are read. By passing them through the filter of something as elusive as the collective or the individual identity, they give rise to points of connection but also of points of rupture, evincing the struggle to maintain often contrasting and purportedly hegemonic narratives.

1.Estévez, F. (2010) «Archivo y memoria en el reino de los replicantes», en Estevez, F. & Santa Ana, M. (eds.) (2010) Memorias y olvidos del archivo. Madrid: Museo de Arte Reina Sofía.

9th November 2017 to 18th February 2018

TEA Tenerife Espacio de las Artes. Sala B

Avda. San Sebastián, 10. Santa Cruz de Tenerife. Tel: 922 849 090 Horario: M-D de 10:00 a 20:00 h.

Archive: CFIT, Biblioteca Provincial, Museo Municipal de Bellas Artes, Imágenes de uso Libre, Gordon Matta-Clark Cortesía de Electronic Art Intermix.

Curated by Gilberto González

It Is No Dream (No es un sueño)

Ammar Younis, de la serie «From The Refugees Photographs. Greece, 2016» (2016)

Is it possible to distinguish a dream from reality?

The question that has been bothering the human mind throughout its existence was the ground for Descartes’ doubt about the ability to rely on sensorial impression. With the birth of the photographic image, it was believed that photographs could provide the evidence of reality. Franz Kafka’s dystopian Metamorphosis opens at a moment of awakening, when its protagonist, Gregor Samsa, discovers that he has been transformed from a man into an insect, and he asks himself, “What happened to me? … it is no dream.” His consciousness can distinguish between reality and dream, however, the existence of human self- awareness in an insect’s body creates a deep sense of uncertainty. Kafka’s “It is no dream” can be read as a counterpoint to “If you will it, it is no dream”, the sentence that concluded Theodor Herzl’s utopian fictional text The Old New Land (Altneuland), whose Hebrew title gave the city of Tel Aviv its name and the State of Israel its agenda and its belief that one can convert dreams into reality.

The exhibition It Is No Dream shifts between, on the one hand, the self- awareness that an irritating reality is not always just a nightmare and, on the other, the illusion that ctional visions can become real. The exhibition also questions the role of the image in the creation of those two points of view.

9th November 2017 to 18th February 2018

TEA Tenerife Espacio de las Artes. Sala B

Avda. San Sebastián, 10. Santa Cruz de Tenerife. Tel: 922 849 090 Horario: M-D de 10:00 a 20:00 h.

Artists: Michal Baror, Ohad Hadad & Hillal Jabareen y Ammar Younis.

Curated by Sigal Barnir

Before is Now–Ko Muri Ko Nāianei [Antes es ahora]

Dieneke Jansen, 90DAYS+: Why is it Necessary for You to Move? (2017)

Before is Now—Ko Muri Ko Nāianei presents the work of three artists working with photography and moving image, using techniques of documentary practices to share narratives that are both highly personal and common. The artists’ work is focused on quite different subjects— cultural and community histories and environmental protection; gentrification, social justice and the rights of government housing tenants; and the involvement of Japan in the Asia Pacific Theatre of War of Word War Two. Drawing on archival footage, testimonies, oral traditions and generational knowledge that is typically tied to specific places, the works present personal and collective narratives that through their specificity often run counter to those commonly accepted. The artists share an approach that is committed to maintaining deep relationships with the past, present, and the future, with people and in connection to place and history. In presenting this work the exhibition considers the archive as a relationship; the archive as something we are in relation to, and with.

9th November 2017 to 18th February 2018

TEA Tenerife Espacio de las Artes. Sala B

Avda. San Sebastián, 10. Santa Cruz de Tenerife. Tel: 922 849 090 Horario: M-D de 10:00 a 20:00 h.

Artistas: Fiona Amundsen, Dieneke Jansen y Natalie Robertson.

Comisariada por Charlotte Huddleston

Dwarf Epics

Zilia Sánchez, Soy Isla compréndelo y retírate (2000)

Today we seem to have reached a general consensus that the current function of the museum is to provide a context in which to frame historic processes. Yet as a context in its own right, as a formal and ideological device, what sort of explanation does a provincial museum like the Municipal Museum of Fine Arts propose? To what extent does it copy a museum from the metropolis? What value is there in the copy? What discourse does it expound and what image does it convey?

Épicas enanas (Dwarf Epics) wishes to heightened the already generalised state of paranoia in which we nd ourselves as an audience. The questions we, insofar as spectators, ask ourselves when we enter a museum, can usually be inscribed within a spectrum that spans from the institution’s pedagogic remit to the power structures that subtend it. It strikes us as paradoxical that by taking on the mantle of custodians of the canon, of staunch beacons of the greatest of our supposedly collective achievements and failures, they become caught up in a rat race that turns them into willing chameleons that justify their own existence and quell any debate.

By overlayering photography, lm, video and the museum’s own collection, we will set in opposition different formal and indeed narrative processes. The idea is to uncover the museum’s legitimising function and reveal how images ultimately seek to modify and control the very territorial and social structure in which they are inscribed.

9th November 2017 to 25th February 2018

Museo Municipal de Bellas Artes

Calle José Murphy, 12. Santa Cruz de Tenerife. Tel: 922 609 446 Horario: M-V de 10.00 a 20.00 h / S-D y festivos 10.00 a 15.00 h.

Artists: Teresa Arozena, Tony Cruz, Equipo Neura, Sofia Gallisá, Werner Herzog, Pablo León de la Barra, Silvia Navarro y Ágata Gómez, Pérez y Requena, Zilia Sánchez, Beatriz Santiago, Juan Carlos Batista.

COFF: Hans Bellmar, Bernd & Hilla Becher, Tacita Dean, Candida Höfer, Evelyn Hofer, Dorothea Lange, Ana Mendieta, Allan Sekula, Lorna Simpson.

TEA: PIC, Man Ray, Thomas Ruff; CFIT: Gerhard Richter

Colección Museo Municipal de Bellas Artes de Tenerife

Residencia Tarquis-Robayna: Adrián Alemán

Curated by Gilberto González

Monsters and fossils

Reykjavik, Mar , Nkisi, The Smartphone (2017)

The idea that we are living in an era saturated with images has become a cliché that has led to a discursive void around the photographic archive. Going beyond any merely iconoclastic critique, a more profound reflection would force us to ask ourselves what images will remain and what images will be lost. To this end, we could imagine the simile of the evolution of the species, in which, in order for some species to perpetuate themselves many others have to die off. In our archaeological endeavour, we will be guided by petrified figures which we will use to construct questionable linear histories. Do we construct images with the same narration we use to give meaning to fossils?

Monstruos y fósiles [Monsters and Fossils] is based on the briefly outlined relationship between archaeology and language, positing a transition to the world of images. At the same time, it explores what in all probability will be an increasingly more pressing problem: the dificulty of classifying and delimiting images in the world. Unquestionably, the screen overwhelms us with its monstrous continuum, but we ought to ask ourselves the question: Is the screen truly an image without a future?

9th November 2017 to 30th December 2017

COAC Colegio Oficial de Arquitectos de Canarias. Planta alta.

Plaza Arquitecto Alberto Sartoris, 1. Santa Cruz de Tenerife. Tel: 822 010 200 Horario: M-V 16:00 a 20:00 h y S de 10:00 a 14:00 h.

Artists: Cristina Garrido, Mar Reykjavik, Antonio R. Montesinos, Ricardo Trigo y Juan José Valencia & Lena Peñate COFF: Tacita Dean.

Curated by Néstor Delgado Morales

She had an umbrella so I supposed it was raining.

A true-to-life essay on reflection, interference and Photography.

In 1889, Peter Henry Emerson argued that we had got so used to photography that we were no longer conscious of what it meant because our critical faculty did not have the tools to understand a medium that is constantly being reinvented and thus prevents us from seeing what it has done and is doing in all facets of life.

To analyse photography (a constant ever since its invention) implies doing so with and from an entelechy that, like this unreal agency, circulates freely, cutting across spaces of perception, which is to say all spaces, without seeking permission. As such, photography is, now and always, a question of belief whose constructs and derivative histories are more or less credible, in the same way that opening an umbrella does not mean that it is raining however much this is what we are led to believe and to expect.

At the current moment, the difference and the fundamental question is that all photos are now in the public domain. They no longer belong to the private or symbolic sphere, nor to advertising or information, and not even to science. Now, and it will never be any different from now on, both the production and perception of photography belongs to all humanity. And this is without doubt a sea change.

9th November 2017 to 8th January 2018

SAC Sala de Arte Contemporáneo

Calle Comodoro Rolín, 1. Santa Cruz de Tenerife. Tel: 922 479 313 Horario: L-V 11:00 a 14:00 h y de17:00 a 20:00 h.

Artists: CCOFF: Berenice Abbott, Sophie Calle, Walker Evans, Michael Kenna, Vik Muniz, Irving Penn, Richard Prince, Cindy Sherman y Alfred Stieglitz

CFIT: Teresa Arozena, Carma Casulá, Francesc Català-Roca, Joan Fontcuberta, Frank Kalero, Mataparda y Enrique Sánchez

Curated by Lola Barrena

Reality is one

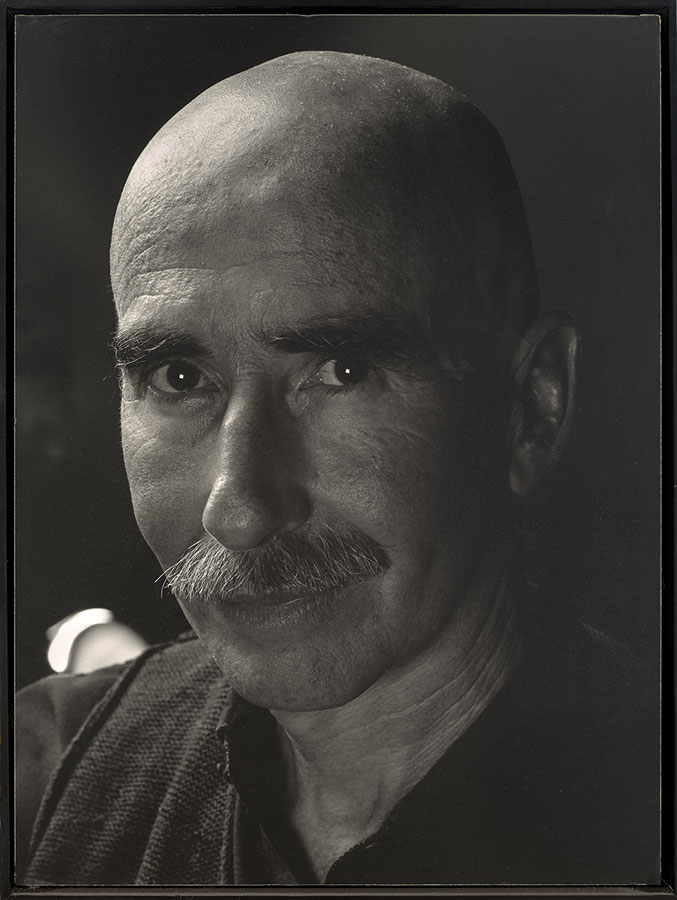

Poldo Cebrián, Retrato de Efraín Pintos (2002)

La realidad es una sola [Reality is One] recovers the output of the photographer Efraín Pintos from his extensive photographic archive. Pintos has largely focused his practice on reproductions of artworks and architecture. This artist’s images can be leveraged to graphically recompose the most significant cultural landmarks in our recent history, making his work central for any proper understanding of the cultural history of art in the Canary Islands.

As soon as he moved to the Canaries in 1971, Pintos actively introduced himself in its cultural life, taking part in several projects associated with the headquarters of the recently opened Oficial College of Architects of the Canary Islands, alongside the critic Eduardo Westerdahl and the architect Vicente Saavedra. These projects included the exhibition Homage to Josep Lluís Sert in 1972 and the first International Sculpture in the Street Exhibition in 1973.

Adopting a retrospective optic, this exhibition overviews forty-six years of the artist’s professional practice. Hundreds of books, catalogues and journals featuring his work are used to compose a broad-ranging and invaluable documentary legacy which serves as the core axis of the show. His photos are an essential component of countless major public and private publications.

9th November 2017 to 10th December 2017

Sala de Arte del Instituto de Canarias Cabrera Pinto

Calle San Agustín, 48. La Laguna. Tel: 922 574 746 Horario: M-V de 11:00 a 14:00 h y de 17:00 a 20:00 h / S-D 11:00 a 14:00 h

Artistas: Efraín Pintos.

Comisariada por Fernando Pérez

Organizan

Colaboran